Until the very end of the nineteenth century, it was hard for readers to differentiate between scientific writing and creative writing being as both shared florid descriptions and personal perspectives, which we have come to assume should only exist within fiction.

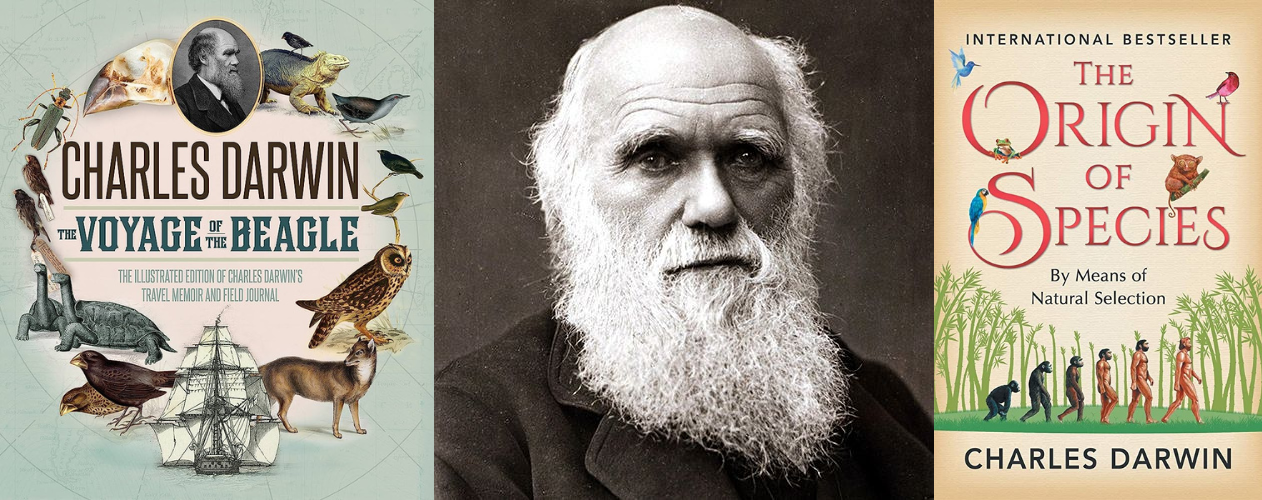

Charles Darwin‘s The Voyage of the Beagle, on which he spent five years of his life circumnavigating the world, is a particularly good example. In it, he often describes the places he visits anecdotally. In Cape Verde, he comes across, for example, an island that “would generally be considered as very uninteresting” and when in Santo Domingo refers to the town as “possess[ing] a beauty totally unexpected from the prevalent gloomy character of the rest of the island.”

While we understand that Darwin’s work would shortly herald a revolution in scientific thought, it is correct to say that his writing reflects a tradition extending from Aristotle, who wrote of animals’ characters rather than physiology (Dolphins, for example, exhibited a “gentle and kindly nature”), through Newton, who was unable to explain “who sets the planets in motion,” and up to the very end of the nineteenth century.

While the scientific precision available to us today was unknown, and unprecedented, scientists like Darwin did realize that they were on the precipice of a great change. Darwin hinted at this in his On the Origin of Species where he wrote that there is “scarcely a single point is discussed in this volume on which facts cannot be adduced.” The idea that facts can be interpreted or “adduced” through speculative reasoning makes his text pre-scientific, but the fact that he adds a disclaimer about how he, and the reader, may reach their conclusions confirms that he is well aware of his own limitations.

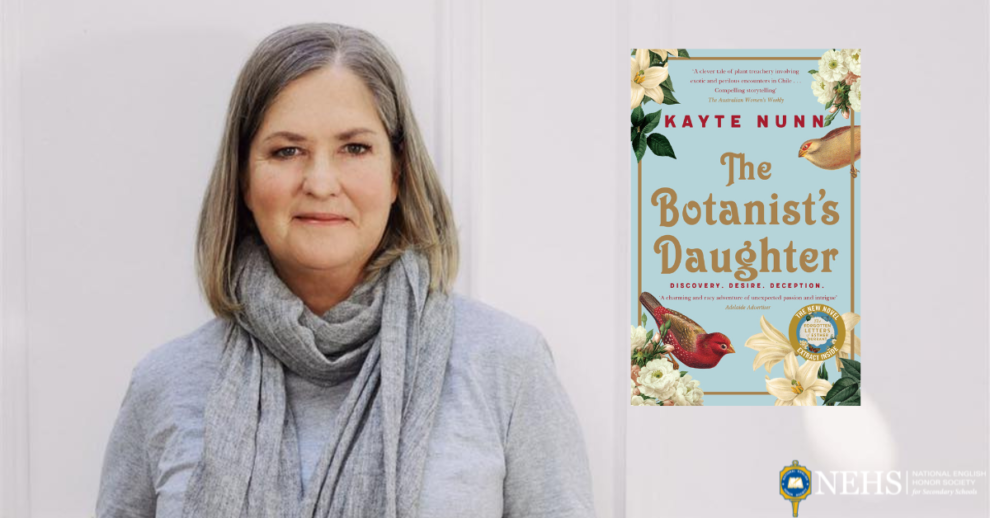

This year’s Common Reader incorporates similar features of pre-scientific writing into its discussion of nineteenth-century botany and, too, hints at the coming scientific revolution: “The mysteries of the natural world are waiting to be unraveled, like pages in a book yet to be read.” As Victorian protagonist Elizabeth travels to South America to research, and re-search for, the elusive Midnight Rose, she realizes that “every leaf, every flower, every blade of grass holds a story waiting to be discovered.”

Her search for an antidote to the most powerful of poisons, the preparation of which is only known through hear-say and local tradition reflects the pre-scientific traditions of Darwin. In contrast, the twenty-first century protagonist Anna Fitzgerald uses the best scientific minds available at Kew Gardens in London to close the “gap between ignorance and enlightenment, [and to] shed light on the myster[y]” of the Midnight Rose.

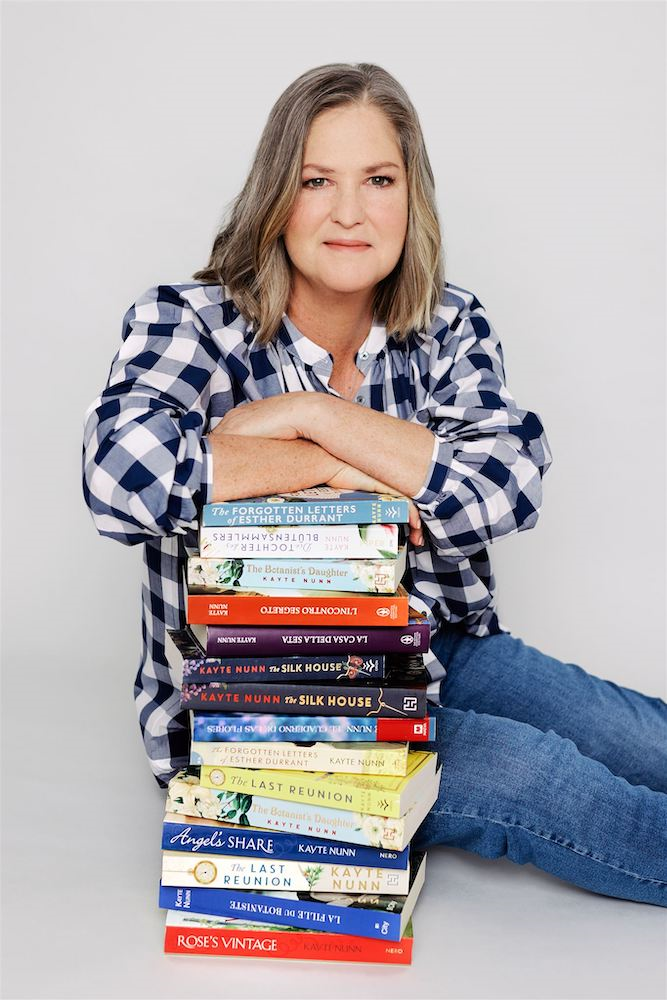

Thus, just like Darwin, Kayte Nunn‘s The Botanist’s Daughter allows the contemporary reader to “to question, to explore, and to embrace the unknown” within the plot while reveling in the luxurious, anecdotal descriptions of the “rhythm and harmony” of the pre-scientific world.

National English Honor Society

The National English Honor Society (NEHS), founded and sponsored by Sigma Tau Delta, is the only international organization exclusively for secondary students and faculty who, in the field of English, merit special note for past and current accomplishments. Individual secondary schools are invited to petition for a local chapter, through which individuals may be inducted into Society membership. Immediate benefits of affiliation include academic recognition, scholarship and award eligibility, and opportunities for networking with others who share enthusiasm for, and accomplishment in, the language arts.

America’s first honor society was founded in 1776, but high school students didn’t have access to such organizations for another 150 years. Since then, high school honor societies have been developed in leadership, drama, journalism, French, Spanish, mathematics, the sciences, and in various other fields, but not in English. In 2005, National English Honor Society launched and has been growing steadily since, becoming one of the largest academic societies for secondary schools.

As Joyce Carol Oates writes, “This is the time for which we have been waiting.” Or perhaps it was Shakespeare: “Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer . . .” we celebrate English studies through NEHS.

National English Honor Society accepts submissions to our blog, NEHS Museletter, from all membership categories (students, Advisors, and alumni). If you are interested in submitting a blog, please read the Suggested Guidelines on our website. Email any questions and all submissions to: submit@nehsmuseletter.us.